As the popularity of women’s sports skyrockets, injuries among women athletes are increasing. Experts say the fact that their shoes and other equipment aren’t designed specifically for women is partly to blame. Engineers are working to address these issues.

By Sandra Guy, SWE Contributor

Candace Parker, the Las Vegas Aces forward whose 16-year professional career includes two Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) championships, took a literal and figurative big step forward at the WNBA All-Star Game this past summer. During the game’s celebrations, Parker, in partnership with the global sports company Adidas, released the first athletic shoe designed by women for women athletes.

The shoe represents the forefront of a new women-led movement to give women athletes more wearable gear choices to improve their comfort, safety, and performance.

Nicole Demby, assistant manager for footwear innovation at Adidas, said her team uses data and insights from elite collegiate and professional women athletes to design its shoe line called Exhibit Select. This data helps ensure that future iterations of Adidas’s women-specific athletic shoes continue to provide women athletes with the support and comfort they need to succeed.

“We’ve done tons and tons of foot scans. We know that women’s feet are 4% narrower than men’s, for example,” said Demby, who earned a B.S. in mechanical engineering at Colorado School of Mines and an M.S. in sports product design at the University of Oregon.

Exhibit Select is designed with a soft neoprene bootie upper and a bounce-cushioning system that sits low to the ground for on-court precision and stability. It is built in two parts in response to women athletes’ long-standing requests for a more flexible, less stiff shoe. Foam helps the shoe feel lightweight and provides the cushion. Available in low-top and mid-top styles, the shoe started selling August 1, 2023, on the Adidas website and at retail for $110 to $140 a pair. Several WNBA athletes have their own player-edition colorways of the shoe, but Parker’s purple and gold “Game Royalty” model was the first available at retail.

“Our innovation team knows that this model is a really good foundation,” Demby said. “We’ve just begun to scratch the surface of women’s basketball. We want to chip away at that research gap and keep unlocking answers.”

Demby said she was motivated partly because she herself was forced to play in ill-fitting men’s or boys’ basketball shoes growing up; those were the only options available. She was wearing men’s basketball shoes when she tore her anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) in high school, forcing her to miss the rest of the season. She was also wearing men’s shoes when she injured that same knee again eight years later while playing as an adult.

Women athletes from youth through professional levels experience as much as eight times more season-ending ACL tears than their male counterparts, research shows. The rate of female ACL injuries is 3.5 times greater than the male rate in basketball and 2.8 times greater in soccer, according to a report from the National Institutes of Health (“The female ACL: Why is it more prone to injury?,” Journal of Orthopaedics, June 2016).

The most common causes of ACL injury are decelerating, landing from a jump, or planting and pivoting off one foot. Claims made by footwear companies that their shoes reduce ACL injuries are difficult to prove, but Demby noted that the first step in reducing the injury gap in women athletes is proper fit. And that requires research. “I said, ‘We need to take this on and figure out why,’” Demby said. “There are so few studies on women basketball players. No one is paying attention to these athletes.”

Expert opinions differ as to why women are more prone to ACL injuries. The latest research steers away from what some deride as blaming women’s “hips and hormones” to look instead at inequities in women’s training, women’s reduced access to high-quality equipment, the higher number of games played versus men, a lack of coordination among women’s teams’ medical and performance staffs, and a lack of comprehensive surveillance studies to find a more definitive answer. A study by Holly Silvers-Granelli, Ph.D., published in the International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy (August 1, 2021), noted: “There is a significant disparity in training, coaching, and competitive resources in female sports. Despite the advent of the Title IX Educational Amendment in 1972, which prohibited sex discrimination in any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance in the United States, there is an incongruency in what females are afforded in competitive sporting environments.”

Companies such as Adidas are aiming to resolve that incongruency, leveraging their research expertise and women athletes’ willingness to experiment to try to prevent injuries.

A growing field

Young engineers working on projects that are centered on women’s athletes speak excitedly about doing meaningful work — and having fun. Their efforts to design shoes, bats, helmets, and ski boots just for women attract social-media buzz from today’s emerging stars in professional soccer, softball, and basketball.

Demby said her engineering background prepared her to speak up about the Adidas women’s basketball shoe priorities and to act as the quarterback for a team comprising a designer, a developer, and a biomechanics scientist. In fact, Demby’s master’s thesis focused on the need for a women-specific shoe. “I was very vocal about my passion for women’s basketball,” she said. “When I started, the brand noticed the need for this project and allowed me to lead it.”

But this wasn’t just a passion project; well-designed women’s sports equipment is big business, reflecting the growing popularity and marketing potential of women’s professional sports.

Viewership for nationally televised WNBA basketball games is up 67% over last year across ABC, CBS, ESPN, and ESPN2 channels, the WNBA reported in June. The average audience of 556,184 viewers per game has put this year on track to become the most-watched regular season in more than 20 years. The WNBA App’s monthly active users have soared by 147% year-over-year.

And sponsorship has reached an all-time high.

Similarly, the women’s National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA) March Madness tournament saw viewership jump 42% percent this year from the 2022 season.

The same trend is emerging in women’s soccer, where the FIFA Women’s World Cup in Australia and New Zealand was forecast to set record attendance and viewership numbers. That’s despite the fact that some games aired as early as 3 a.m. Eastern time in the United States. More than 2 billion people were expected to watch the Women’s World Cup, up from 1.12 billion in 2019. And women’s club football (soccer in the United States) stadium attendance for 2022 in top leagues exceeded pre-COVID-19 levels, according to Euromonitor International’s analysis.

Playing ball

The need for women-specific gear extends into softball as well. Rawlings Sporting Goods, whose name is synonymous with baseball gloves, is a 136-year-old American sports equipment maker based in St. Louis. Rawlings is taking steps to make sure its batters’ helmets deliver improved performance for women playing softball.

Becky O’Hara, director of research and development at Rawlings, said the company’s newest innovation is a batter’s helmet face mask that helps women who play fast-pitch softball see more clearly. The stainless-steel face mask, dubbed the Mach Hi-Viz, features two bars that protrude from each side of the mask, leaving a gap in the middle of the player’s face. The typical face mask has a bar that goes all the way across a player’s face underneath the eyes. With this new design, O’Hara said, “The players can look straight ahead and down,” making for a clearer view of the ball as it gets hurled from the pitcher’s mound.

The Mach Hi-Viz retails for $79.99, a modest increase from the $69.99 price of Rawlings’s previous fast-pitch softball helmet.

O’Hara, who played on the girls’ softball team and the boys’ ice hockey team as a defenseman in high school, and on the women’s ice hockey team in college, earned a B.S. in mechanical engineering at McGill University and an M.S. in mechanical engineering at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. She wrote her master’s thesis on how bat properties such as weightings and handle and barrel flexibility affect a bat’s performance. Now she enjoys working on fast-turnaround innovations for products that she and her children can enjoy. At Rawlings, she said, a product cycle usually lasts one to two years, including making prototypes and testing them. “The next thing you know, you can see the products on TV,” O’Hara said.

Rawlings is also developing female-specific catching gear, focused on fitting a woman’s body. And the company is working on a lighter bat for those who play slow-pitch softball.

Like Adidas, Rawlings has started partnering with women athletes to design its female-focused gear. They include Jen Schroeder, a former softball player with the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Bruins, who now runs her own catching training center; Sierra Romero, a professional softball infielder with Athletes Unlimited; and Jocelyn Aloha Pumehana Alo, a four-time collegiate All-American and two-time national championship winner who plays utility (multiple positions) for the Oklahoma City Spark professional women’s softball team.

Right from the source

As more companies seek experts in the design of sporting gear for women, more universities will need to graduate experts in this field. Lowell, Massachusetts, once a prosperous textile-mill town, is now known as the site of one of the country’s top national sports research universities.

The University of Massachusetts Lowell runs a Baseball Research Center and the Sports Collaborative for Open Research and Education (SCORE) — and will offer a sports engineering minor starting this fall.

Patrick Drane, assistant director of the Baseball Research Center, said he spearheaded the minor because sports engineering is a growing field. He noted that sports data analytics and related skills are in demand, and sports engineers operate and develop the technologies that track and feed that data.

“Even if students aren’t going into the sports industry, the sports engineering way of looking at high-performance materials is very relevant to lots of other industries,” said Drane, who holds a B.S. and an M.S. in mechanical engineering.

Sociological factors combined with technical design will be a key concept in the minor, said Kari White, mechanical and industrial engineering assistant teaching professor at UMass Lowell’s Francis College of Engineering. She said students will be taught to consider the consumer, their own initial assumptions, the socioeconomic implications of their work, the source of their data, and the lens through which they will review their data. They may also study the history of race and gender in sports.

On the technical side, White teaches applied finite element analysis and computer simulations in the design track. “Instead of building the part, students can simulate it in a computer model,” said White, who has designed a manufacturing process for U.S. Army helmets. She holds a B.S. and an M.S. in mechanical engineering and is now defending her Ph.D. in mechanical engineering. Using computer simulations is a more efficient way to design, she explained. “We can test more variations and make changes in the model.”

At Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) in Worcester, Massachusetts, Christopher A. Brown, Ph.D., a mechanical engineer and a former All-American ski racer, is leading an effort to design a horizontally split-sole shoe with a load-limiting spring system to keep athletes from tearing their ACLs.

He compared the spring, which has received a provisional patent, to a car’s suspension system. The technology goes between the part of the shoe that touches the ground and the part that touches the foot, absorbing weight load shifts to keep the wearer from injuring a knee or ankle.

Dr. Brown, who teaches graduate courses in axiomatic design and surface metrology, and undergraduate courses in manufacturing and the technology of alpine skiing, said he was inspired to research ACL injury disparities when he read the book Warrior Girls: Protecting Our Daughters Against the Injury Epidemic in Women’s Sports by journalist Michael Sokolove (Simon & Schuster, 2008).

Dr. Brown said he found the situation with women athletes’ injuries concerning. But he realized that because America has no publicly funded sports science institutes like those in Oslo, Norway, and Salzburg and Innsbruck, Austria, it would be more difficult to do this kind of research in the United States, where such research is largely privately funded.

Dr. Brown has partnered with Sports Engineering, Inc., a New York-based company, to patent the shoe load-management technologies that result from his WPI classes’ continuing research.

Josephine Bowen, a former WPI ski racer who now races in a master’s league, helped prototype and develop the shoe spring in Dr. Brown’s classroom. She holds a B.S. and an M.S. in mechanical engineering from WPI, and said she learned in class that she wants to design prosthetics and medical devices to help athletes with otherwise career-ending injuries stay in competition.

Separately, Danyon Loud, a sports engineering doctoral student at The University of Adelaide in Australia and a soccer player and coach, is testing women’s football boots (often called soccer cleats in the United States) that are already on the market to see whether and how they differ from men’s soccer footwear.

So far, Loud, who has coached women’s soccer teams for the past six years, has yet to find a women’s shoe that he believes offers the level of safety that professional women players deserve. “It’s not just the fact that women’s feet are different in shape and length from men’s,” he said. “Women’s feet tend to be wider at the toes and narrower at the heels.” After he earns his Ph.D., he aims to advise companies and practitioners on how to improve women’s shoe molds and designs.

Loud, who earned an honors B.E. in mechanical and sports engineering at The University of Adelaide, said he is especially concerned that today’s shoes focus greatly on performance and increased levels of traction. Those factors can pose an injury risk as players are more likely to get stuck on the playing surface.

“Movement itself can be a predictor of lower-limb injuries,” he said. “One example is the knee position of a landing athlete, or the area of the landing foot and its degree of flexion. This emphasizes that a holistic approach is needed to form a relationship between the players’ footwear and how they move.”

Though women continue to search for proper sports shoes — some even go to the children’s section to find shoes that fit — Loud said he urges them to stay positive.

“Changes are coming,” Loud said.

Change cannot come too soon. Research from the European Club Association showed that more than 80% of female players at Europe’s elite clubs have suffered regular discomfort because of their football boots. The research surveyed 350 players from 16 top-tier teams. Some 82% of respondents said the discomfort they felt could hurt their performance, and one-fifth said they customized their own boots to try to make them fit better.

The data also showed that 34% of women players, who were surveyed anonymously, reported discomfort in their heels. The heel discomfort was significantly higher among Black players (48%) than white players (32%).

A strong legacy

Women designing sports gear for women may be relatively rare, but it is nothing new.

On May 6, 2022, three women who worked together to create the first sports bra were inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in Alexandria, Virginia.

Lisa Z. Lindahl, Polly Palmer Smith, and Hinda S. Miller created the bra — then called the Jogbra — in 1977.

Lindahl, who had earned a B.S. in education at the University of Vermont in 1977, had started running 30 miles a week. She and her sister, also a runner, were talking on the phone one day about how uncomfortable traditional bras were — as Lindahl put it, “bouncing breasts, straps that fell off and ill-fitting bras” — when her sister said, “Why isn’t there a jock strap for women?”

“We laughed,” Lindahl said. “And I thought, ‘Yes, why isn’t there?’”

Lindahl’s husband overheard this conversation and bounded down the stairs wearing a jockstrap pulled over his head and onto his chest.

“I took it off him and pulled it over my head, putting the cup of the jock strap over one [breast],” Lindahl said. “And I said, ‘Oh my gosh, maybe we’ve got something.’”

Lindahl made a list of what she wanted: a bra that didn’t chafe, was breathable, provided adequate support, had straps that would stay up, and had no hardware that would dig into the skin.

Smith, who had been friends with Lindahl since they were in eighth grade, happened to be renting a room from Lindahl that summer. Trained as a costume designer, Smith was working in a Shakespeare festival in Burlington, Vermont. Lindahl asked Smith to sew a prototype. Smith sewed two jock straps together, and that became the bra’s first layer of elastic. Smith then found a breathable fabric for the cups.

“Up until that time, no bras went over your head or had cross-straps in the back,” Smith said.

Miller, then a costume design student in the same Master of Fine Arts program as Smith at the New York University Tisch School of the Arts, was working with Smith as an assistant designer at the festival. She took the prototype to a swimsuit designer, who tweaked the bra’s design, and then to a mom-and-pop manufacturer.

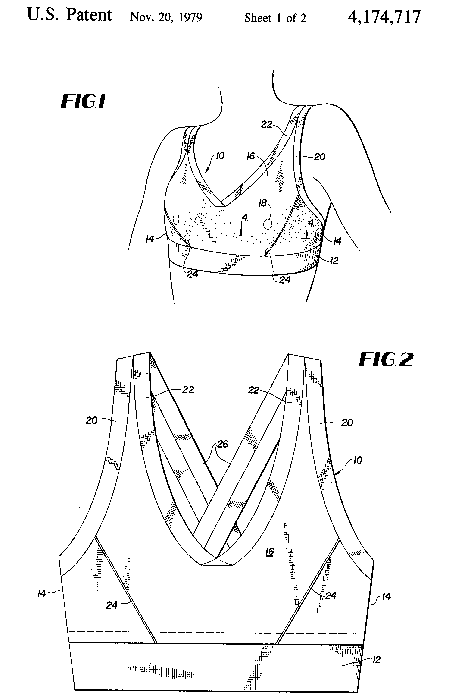

Patented in 1979, the sports bra was commercialized as the Jogbra, featuring a seamless, compressing front panel, non-chafing exterior seams, crossing elastic straps, and a wide elastic rib band.

Lindahl founded Jogbra Inc., later renamed JBI, in 1977. She served as CEO until 1990, when the company was sold to Playtex Apparel, which later sold it to Sara Lee, where it became part of the Champion brand.

In 2001, Lindahl, who had been diagnosed with epilepsy at age 4, co-created the Bellisse Compressure Comfort Bra, a patented breast and chest compression garment for breast cancer patients and survivors.

Lindahl earned an M.S. in culture and spirituality at Holy Names University in 2007, and she writes books, notably Unleash the Girls: The Untold Story of the Invention of the Sports Bra and How It Changed the World (And Me) (Bublish, Inc., 2019).

Smith went on to win eight Emmy Awards, mostly for her design work with The Jim Henson Company in movies such as Labyrinth, Muppet Treasure Island, A Sesame Street Christmas Carol, and The Dark Crystal.

And the sports bra innovation remains a touchstone.

“It changed the world,” Lindahl said. “We are interviewed to this day about the impact of the sports bra. It is essential in the support and empowerment of female athletes. It has become a feminist icon.”