Many of the most prominent whistleblowers in the technology sector have been women. What does it take to become a whistleblower, how are you perceived — and what happens next?

By Christine Coolick, SWE Contributor

If you were inappropriately propositioned by your manager, how would you react? If you learned your employer was treating its users unethically, what responsibility might you feel? If you witnessed a hostile or discriminatory work environment, what would you do?

Would you blow the whistle on the company’s practices?

Whistleblowing’s evolution

The concept behind whistleblowing is twofold: that a problem within an organization is too much of a societal issue to ignore and that it can’t be resolved — or won’t be resolved — by the organization itself.

Historically, when whistleblowers go public, the perception has been negative — seen as equivalent to an employee betraying their organization.

“Society sort of looked at whistleblowers as rats, snitches; a lot of really negative terminology was associated with whistleblowers,” said Siri Nelson, J.D., executive director of the National Whistleblower Center, a nonprofit that provides legal assistance to whistleblowers and advocates protection laws.

More recently, however, perceptions about the act of whistleblowing — and whistleblowers themselves — have changed, thanks in large part to federal-level protections such as the Whistleblower Protection Act of 1989, the Dodd-Frank Act and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission SEC whistleblower program (both of which began in 2010), and the Whistleblower Protection Enhancement Act of 2012.

These laws helped change the narrative. “They incentivized people to come forward and helped them to stop major potential issues with the economy, with public health, and with so many different areas,” said Nelson.

“Once the government started to see how powerful whistleblowers are to advancing government interests, they just started celebrating,” said Nelson. “They saw how much money whistleblowers were helping them recoup, and how much fraud whistleblowers were stopping from getting to the worst possible outcome, and how much whistleblowers were protecting investors.”

With billions coming in from multimillion-dollar sanctions because of whistleblower disclosures, Nelson said, the government took on a decidedly positive stance toward whistleblowers. In fact, since 2013, Congress has recognized July 30 as National Whistleblower Appreciation Day.

“Whistleblowers have become viewed as champions,” Nelson said.

And public perception and media portrayal of whistleblowers have followed. Societal perception has shifted so drastically, in fact, that a 2020 Marist Poll commissioned by Whistleblower Network News found that an overwhelming majority of Americans — 86% — strongly believe that whistleblowers who report corporate or government fraud should receive protection. Eighty-two percent of poll respondents also thought Congress should prioritize passing stronger laws to protect employees who report corporate fraud.

Support for whistleblowers is now more plentiful. In addition to the National Whistleblower Center, Whistleblowing International works globally to support whistleblowers, investigate corruption, and advocate whistleblower rights. The Southeast Europe Coalition on Whistleblower Protection, the European Center for Whistleblower Rights, and the Center for Whistleblower Rights & Rewards are other examples of the organizations providing assistance. In the United States, the Department of Labor’s Whistleblower Protection Program (whistleblowers.gov) now enforces more than 20 statutes that protect whistleblowers from retaliation from their employers and provides other resources.

The influence of gender

All of this support doesn’t mean, however, that blowing the whistle is easy. After all, in 2019, technological research and consulting firm Gartner reported that nearly 60% of all misconduct observed in the workplace is never reported. The main reason is fear of retaliation.

“For some, the damage caused by retaliation can last for years … and can be a result of the prolonged exposure to workplace traumatic stress and a hostile environment,” wrote Jacqueline Garrick in a blog post for the National Whistleblower Center. Garrick is herself a whistleblower and founder of Whistleblowers of America, a peer-to-peer support network for whistleblowers.

So what does motivate a whistleblower to step forward? And does their gender make them more or less likely to do so?

In June of this year, two University of Massachusetts Amherst researchers posed the question in The Conversation: “Why are so many big tech whistleblowers women? Here is what the research shows.”

Francine Berman, Ph.D., director of public interest technology and the Stuart Rice Research Professor, and Jennifer Lundquist, Ph.D., professor of sociology and senior associate dean of research and faculty development, wanted to explore the data around gender and whistleblowing. They recognized that this research is particularly challenging because the majority of whistleblowing is done anonymously or confidentially.

“Once the government started to see how powerful whistleblowers are to advancing government interests, they just started celebrating. They saw how much money whistleblowers were helping them recoup, and how much fraud whistleblowers were stopping from getting to the worst possible outcome, and how much whistleblowers were protecting investors.”

–Siri Nelson, J.D., executive director, National Whistleblower Center

And yet the ones who made headlines were hard to ignore: Frances Haugen; Timnit Gebru, Ph.D.; Rebecca Rivers; Janneke Parrish; Susan Fowler. Their names were in the news the past few years for blowing the whistle on questionable practices at companies such as Meta, Google, Apple, Uber, and more. All were women and all were big-tech companies.

Other industries have had their fair share of high-profile women whistleblowers as well, going back decades: Cynthia Cooper at WorldCom; Sherron Watkins at Enron; Coleen Rowley, J.D., at the FBI; Bunnatine “Bunny” Greenhouse at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; Allison Gill, Ph.D., the previously anonymous podcaster behind Mueller, She Wrote, at the Veterans Affairs; Kimberly Young-McLear, Ph.D., at the Coast Guard; Erika Cheung at Theranos; Cristina Balan at Tesla.

What made these employees willing to risk their employment, their reputations, and their future job prospects on the act of whistleblowing?

“People blow the whistle because they want to protect what’s right,” said Nelson. “The motivation comes from public interest … it’s from an idea of fairness.”

Drs. Berman and Lundquist explored this motivation of virtue. And they wanted to unpack whether the stereotype is true that women are inherently more virtuous than men, more altruistic and concerned for the interests of the public.

For the public good

This idea that women are more focused on the public good than men is common and not without some data supporting it. The United Nations named the global empowerment of women a critical step in reducing corruption and working toward greater equality. Dr. Berman and Dr. Lundquist note several studies that found a greater share of women in elected office results in lower levels of government corruption. Other studies have found that when it comes to business transactions, women are more ethical than men. This may be due to how women are socialized, they note.

Nelson also sees how gender socializing plays a factor, but in a different way. From her work interacting with whistleblowers, Nelson describes women whistleblowers as “way more fierce than men — way more.”

She suspects this is because women are more often socialized to be quiet. “Women are told to sit down, shut up … that we should be small and silent. That is the exact opposite of what it takes to blow the whistle. So when a woman decides to blow the whistle, she’s already breaking out of the mold. And because you’ve already taken that step, she has thought through it thoroughly. She has full conviction of what she’s going with — without a doubt — and she will not stop until she sees a situation remedied in one way or another.”

Because it is not possible to know the gender of every whistleblower, researchers have used public surveys to determine how likely one might be to report wrongdoing. In their studies, an effect linked to gender wasn’t found. However, women did report being more willing than men to report wrongdoing when they are able to do so confidentially.

Perhaps the most prominent recent example of this is The Facebook Files. Beginning in September 2021, a series of investigative articles published in The Wall Street Journal explored how Meta (then Facebook) was sweeping under the rug scores of concerning data because it might be damaging to the company’s bottom line. An anonymous whistleblower shared tens of thousands of pages of internal documents with The Wall Street Journal. The series explored in vivid detail some of the company’s most damning practices:

- Facebook was allowing high-profile users to be exempt from the platform’s own rules for appropriate content, permitting celebrities to post harassing language, incitements to violence, or wildly inaccurate misinformation.

- According to the company’s own research, Instagram was negatively impacting the mental health of teens.

- Facebook’s algorithm update was amplifying political misinformation.

- The platform was permitting the distribution of violent and graphic imagery.

- Facebook was allowing pages run by violent organizations to help recruit members and even help human traffickers recruit victims.

The tens of thousands of internal documents that formed the basis of the series were also turned over to the SEC, as well as Congress.

The concept behind whistleblowing is twofold: that a problem within an organization is too much of a societal issue to ignore and that it can’t be resolved — or won’t be resolved — by the organization itself.

Then, in early October, former Facebook employee Frances Haugen stepped forward as the Facebook whistleblower.

Haugen began working for Facebook in 2019 as a product manager focused on protecting against election interference on the platform. From the very beginning, she felt her team was given too few resources to really make an impact and quickly grew skeptical of Facebook’s intentions.

Before leaving the company in May 2021, she began reviewing documents on the company’s internal social network, Facebook Workplace, and was amazed at the breadth of information she was able to access.

“The thing I saw on Facebook over and over again was there were conflicts of interest between what was good for the public and what was good for Facebook,” Haugen told “60 Minutes.” “And Facebook over and over again chose to optimize for its own interests like making more money.”

Haugen was motivated to change it.

“When we live in an information environment that is full of angry, hateful, polarizing content, it erodes our civic trust, erodes our faith in each other, and erodes our ability to want to care for each other,” continued Haugen during the interview. “The version of Facebook that exists today is tearing our societies apart and causing ethnic violence around the world.”

On her last day on the job, Haugen wrote her final post to Facebook Workplace: “I don’t hate Facebook. I love Facebook. I want to save it.”

Not an insider

In addition to concern for the public good, women’s motivations to blow the whistle may be linked to their underrepresentation and lack of organizational power, Drs. Berman and Lundquist theorized. At the top five big-tech companies — Apple, Amazon, Google, Meta, and Microsoft — women make up about a quarter of tech workers and about 30% of executive leadership.

Here, Dr. Lundquist explains, women are still a minority, but they are starting to move into middle management. Yet they haven’t been in their positions long enough to be insiders. “That’s where there’s a threshold percentage when women are more likely to be whistleblowers, when they have, in middle management, the power to be able to do the whistleblowing, but also still the outsider status to be able to see the corruption,” she said.

Dr. Lundquist also describes how more recent whistleblowing has been around the treatment of women in these spaces. “A lot of whistleblowing in recent years is linked to issues that women specifically experience, such as #MeToo and discrimination,” she said.

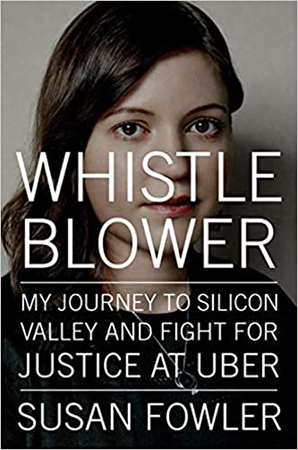

Susan Fowler’s experience at Uber is a prime example of this. Fowler had previously worked in coding for Silicon Valley startups Plaid and PubNub before being recruited by Uber in 2015.

From the beginning, Fowler struggled at Uber to be treated fairly. She watched as other women and minority employees were berated and mistreated by managers. After a year at the company, she quit. Two months later, she wrote a blog post about her experience at the company that quickly went viral.

In the post, Fowler recounted how, on her first day on the job at Uber, her manager sent her sexually harassing messages over the company’s chat app. When she reported this to HR, she was told she needed to move teams because her manager was a high performer and this was his first offense. She soon learned this was the same response a handful of other women received when complaining about the same manager — it was always his first offense.

She recounted how she reported multiple instances of sexism to HR, until they called her to a meeting to note that the common theme in all of the reports she was making was her. She escalated the issue to the head of HR and the chief technology officer, but no action was taken. Feeling at the end of her rope, Fowler took a new job a week later.

After publishing the blog post, it was covered across dozens of news outlets. Multiple investigations into the practices at Uber were conducted, including one by former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder. His final report was scathing. Fowler summarized the findings in her 2020 memoir Whistleblower: “… an organization so dysfunctional and broken that its culture needed to be completely torn down and rebuilt from scratch.” CEO Travis Kalanick ultimately resigned.

The only way, it seemed, for this kind of organizational change to happen was, from Fowler’s experience, to leave — and to blow the whistle.

“It’s important to remember that there are laws that protect us from sexual harassment and discrimination at work,” Nelson noted. And whistleblowers who raise the red flag about these practices are just as important as ones who flag financial crimes.

Ifeoma Ozoma had a similar experience of blowing the whistle on discrimination at Pinterest.

“In many professions such as big tech or engineering, women tend to be a pretty small percentage,” said Dr. Lundquist. “And when they are a small percentage, there’s issues in terms of inclusion, and feeling a sense of solidarity or insider status with the unit or the institution. And so I think people are more likely when they are in that situation to be willing to go public or blow the whistle because they have less to lose because they already don’t feel they’ve ever gained that insider status.”

Toward more diversity and less societal harm

Whistleblowing in big tech may be the result of “a perfect storm between the field’s gender and public interest problems,” Drs. Berman and Lundquist theorized. No research clearly points to why more big-tech whistleblowers are women, but the aim of these whistleblowers is often at “boosting diversity and reducing the harm big tech causes society,” they wrote in their essay.

An experience at Google by a well-respected computer scientist seems to exemplify this perfect storm. Timnit Gebru, Ph.D., joined Google in 2018 to co-lead a team working on the ethics of artificial intelligence (AI).

The team she built there was “one of the most diverse in AI and include[d] many leading experts in their own right,” wrote Karen Hao in MIT Technology Review. “Peers in the field envied it for producing critical work that often challenged mainstream AI practices.”

In December 2020, Dr. Gebru was asked by management at the company to withdraw the paper she had submitted for publication or remove the co-authors’ names who worked at Google. The rationale was that the paper didn’t take into account the latest research on the subject. The paper reviewed the risks of large language models, which are AIs that are trained to produce content by studying enormous amounts of text data. Those risks included the fact that racist, sexist, and abusive language can easily end up in the training data, which could lead the AI model to believe that racist language is normal.

“People blow the whistle because they want to protect what’s right. The motivation comes from public interest … it’s from an idea of fairness.”

–Siri Nelson, J.D., executive director, National Whistleblower Center

When Google asked Dr. Gebru to withdraw the paper, she pushed back, asking who at Google had made this decision, what their rationale was, and for advice on how Google would prefer the paper to be revised. She said if she didn’t receive this information, she would discuss an end date for her employment with them. Their response was quick: They stated they “accepted her resignation” and immediately terminated her employment. She had not resigned.

Dr. Gebru took to Twitter to share what had happened and made public a lengthy email she had shared with colleagues describing the experience. Thousands of Google employees and academics signed a letter condemning her firing. Nine members of Congress sent Google a letter asking for clarification on Dr. Gebru’s employment termination. The vice president at Google who had dismissed Dr. Gebru ended up being let go.

Nelson noted that Dr. Gebru’s experience has another layer of complexity because of her race.

“When you look at how she was treated versus how Frances Haugen was treated, she wasn’t invited to Congress, she wasn’t hailed as some amazing person who’s coming forward with great information,” Nelson said. “She was often portrayed as an angry Black woman who should have been happy with how far she got in the tech industry and who was making things up.”

Unfortunately, said Nelson, when a woman blows the whistle, there is often less of a focus on the material that she’s presenting and more of a focus on her appearance and how much she adheres to gender and racial roles.

Nelson noted that in the cases of Haugen and Fowler, they were able to gain traction in the public eye because they were portrayed in the media in a light that made them seem innocent, approachable, and otherwise timid.

Where do whistleblowers go next?

Dr. Lundquist said there is research that shows that women are more likely than men to have second thoughts and fears around whistleblowing. This is likely because “women tend to get much more stigmatized or are more likely to lose their job,” she said. “The backlash against women whistleblowers tends to be even more intense than that against men.”

This makes it even more striking, Dr. Lundquist noted, that women still appear more likely to be whistleblowers. The small networks they have are usually lost. The psychological impact is great. Those who have gone public, like Fowler, Haugen, and Dr. Gebru, have shared how they have faced severe backlash for their efforts, including online harassment.

Nelson sees firsthand the challenges whistleblowers face. Despite public support and available resources, they are typically blacklisted and struggle to find another job in their industry.

“Blacklisting happens because there’s prejudice against whistleblowers,” she said. “And part of that prejudice has to do with fear — it’s the glass houses issue. Everyone has things that they’re insecure about; every business owner has things they’re worried might get out into the public, for whatever reason. And when they hear about a person who has the experience of speaking out in the public about wrongdoing inside of the company where they work, that to them is a negative quality.”

Unfortunately, she said, “it’s a very rare whistleblower that blows the whistle publicly and is able to continue in their career of choice.”

Fowler left the tech industry, wrote her memoir, and moved into a career as a writer. Haugen too left the technology sector and established her own nonprofit. Dr. Gebru launched her own independent research institute.

Dr. Lundquist said that protections for whistleblowers are incredibly important, as well as a better integration of ethical considerations into our corporate workflow.

The best way for someone who wants to blow the whistle and continue working in the same industry is to do so anonymously, Nelson said. “That’s why anonymity is such an important part of whistleblower programs that are actually successful,” she said. This reduces the likelihood of being blacklisted, being fired, and being retaliated against.

Also important is transparency. “Big tech is so proprietary and so competitive, the lack of transparency is a real issue,” said Dr. Lundquist. “It makes it very difficult for consumers to make decisions to have any autonomy over the product.” And that is what makes whistleblowing so vital. “People aren’t able to see this, except for those who are working within the industry.”

More regulation to make organizations responsible for their users’ behavior might be a way to improve transparency. “Our regulations have not caught up with our digital advances and for technology, transparency is key,” said Dr. Lundquist.

Education is an important component, too, Nelson said. Many tech industry workers are asked to sign nondisclosure agreements. Yet, Nelson said, “It’s illegal to have an agreement that stops you from reporting violations of law, rule, or regulation to the government.” She sees it as a huge problem that so many tech workers believe they are not allowed to speak up.

Nelson’s final hope is that we all become better at supporting people who speak up. “Most whistleblowers I’ve spoken with say that the silencing process starts at the very beginning — the moment you open your mouth and tell anyone that you’re thinking about speaking up is the moment somebody will tell you to be quiet.”

Instead, she said, we need to create space for these conversations. “We need to help foster a culture of speaking up.”

Former FBI Agent and Whistleblower Finds New Purpose

By Marsha Lynn Bragg, SWE Associate Editor

A 2002 TIME magazine cover shows three women — Cynthia Cooper; Coleen Rowley, J.D.; and Sherron Watkins — and refers to them as “The Whistleblowers” for their courage in reporting misdeeds and corruption at the companies where they worked.

Of the three, Watkins is perhaps the best known. She served as vice president of Enron, a major energy company in Houston. She wrote a letter to company chair Kenneth Lay, Ph.D., in the summer of 2001 warning him that the company’s accounting methods managed by Arthur Andersen LLP were improper. Soon after, Enron went bankrupt. Investors lost money and employees received a fraction of their retirement benefits. According to TIME, Enron’s demise was the largest bankruptcy in U.S. history at $63.4 billion. During a congressional subcommittee hearing the following January investigating Enron’s fall, Watkins’ letter was released, pushing her into the public sphere and rebooting the whistleblower phenomenon.

Yet they weren’t the first nor will they be the last.

Whistleblowing has been an important tool against public and private wrongdoing in America since 1863, when Congress passed the False Claims Act (FCA) in response to defense contractor fraud during the Civil War. Whistleblowers were compensated for their risk-taking, oftentimes half of what the government recovered. Congress amended the FCA in 1986 to allow for an increase in reward provisions and to create stronger protections for those who expose wrongdoing. Whistleblowers come from a range of fields: technology, the military, banking and finance, oil and gas, energy, education, health care, law enforcement, insurance. The FCA also protects employees from discrimination, harassment, and suspension or termination of employment as a result of reporting possible fraud.

Yet that is what Jane Turner encountered after she twice reported the FBI for wrongdoing during her 25 years as a special agent.

Turner grew up in Rapid City, South Dakota, and wanted to be a federal agent from the age of 12, a dream that stemmed in part from a childhood experience in her hometown. “As a young person, I remember going down the block to a house where the husband had murdered his wife and family and then committed suicide. I stood outside that house for a long time trying to understand why he did it.”

“I blew the whistle the second time because the FBI did nothing about my first whistleblowing endeavor. I learned that they simply covered up malfeasance and corruption in order to retain and maintain a reputation that was more important to them than enforcing the law.”

-Jane Turner, director and chair, Whistleblower Leadership Council; former FBI special agent

Women were barred from serving in the FBI until after the death of controversial FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. The FBI began to hire special agents from varied backgrounds — including women. Turner, who has a master’s degree in forensic psychology from John Jay College of Criminal Justice, was one of the first 110 women hired. She worked as a special agent and psychological profiler who trained under original FBI profilers Roy Hazelwood; John E. Douglas, Ph.D.; and Bob Ressler. She also received training in Crimes Against Children and SWAT.

Turner led the bureau’s highly successful program combating child sex crimes and crimes against women on North Dakota reservations. In 1998, she discovered that agents in her resident agency were falsifying reports and failing to act on malfeasance in the Turtle Mountain Reservation. The complaint was ignored, she said, yet their “solution” was to move her from Minot, North Dakota, to run the Crimes Against Children program in Minneapolis, despite having a well-respected reputation in Minot and with law enforcement and federal officials.

In the aftermath of the World Trade Center bombing, The Washington Post reported that in August 2002 during the ground zero cleanup and investigation, Turner discovered that a member of the FBI’s elite evidence response team had taken a valuable Tiffany globe from the complex’s wreckage. She put the globe in an evidence bag and turned it over to the Office of Inspector General. Retaliation was immediate. Turner said she was accused of tarnishing the FBI’s image and labeled a troublemaker and a whistleblower. Her once stellar performance reviews were gradually downgraded. She was even forced to retake a fitness for duty exam, which she passed.

“I blew the whistle the second time because the FBI did nothing about my first whistleblowing endeavor,” she said. “I learned that they simply covered up malfeasance and corruption in order to retain and maintain a reputation that was more important to them than enforcing the law.”

Another whistleblower, Fred Whitehurst, Ph.D., J.D., a former FBI scientist who reported on forensic fraud in the FBI crime lab, referred her to attorney Stephen M. Kohn, J.D., a co-founder of the National Whistleblower Center. The nonprofit, nonpartisan Washington, D.C., organization supports whistleblowers worldwide and helps prosecute corruption and other wrongdoing. The center also ensures whistleblower protections remain in federal laws.

With Kohn’s representation, Turner challenged her retaliation in federal court and won, fighting the FBI’s retaliation for nearly nine years. In 2007 a jury awarded her more than $1.5 million, the maximum compensatory damages permitted under Title VII. Her courageous efforts led to an FBI policy that forbids agents from taking items from crime scenes and another that changed resident agency transfers.

“Life is never the same; you lose everything,” she said of her experience after whistleblowing. “I was constructively discharged from the FBI and my dream job was crushed along with my identify and purpose. It took me 10 years to get back on my feet and become productive again.”

Turner regained her purpose after accepting Kohn’s invitation to spearhead the National Whistleblower Leadership Council. In this role she engages and promotes whistleblowers and whistleblowing. She does this via her biweekly podcast conversations with a whistleblower, through her articles in Whistleblower Network News, and involvement in National Whistleblower Day, annually held in July to recognize the contributions of whistleblowers and commemorate the country’s first whistleblower law.

“Whistleblowers are unsung heroes. They are motivated by a higher purpose and believe in the elements of truth, fidelity, and integrity. Their courage is inspiring,” she said, adding that the center’s advocacy makes would-be whistleblowers more willing to expose wrongdoing. “Those are reasons enough to celebrate them.”